Meccanica UHPC ductal concrete install complete.

Szolyd has completed the final touches on the UHPC art piece, “Substation Pavilion” for the Meccanica development by Cressey. Designed by Cedric Bomford, the Szolyd team collaborated early in the design stage to help work out the constructibility details. Lafarge’s Ductal concrete was the obvious choice to create thin modular panels that made for an easy installation. The UHPC panels averaged 3.8 cm thick (1.5″), the largest piece being 13ft long. Integral bolts were cast into the precast components, allowing each piece to snap together like lego.

Usually the Szolyd precast concrete team utilizes fine mold building materials such as rubber and fibreglass. The surface left by these materials, mirror the positive material they are cast against, resulting in near perfect precast concrete. In the case of Meccanica, a rough board formed surface was desired by the artist. Szolyd built the UHPC molds in a classic board formed concrete style. The cedar lining the molds, left this highly refined cementitious material with a rough, more industrial surface texture, exactly as the artist envisioned.

Cedric Bomford

Substation Pavilion, Artist Statement.

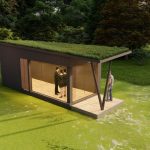

Substation Pavilion consists of a small structure constructed of board-formed Ductal concrete, steel and glass, with a door that hints at a possible entrance (although in this case it is merely a decoy). There are windows on two sides, adding to the illusion of some kind of use value implicit to its presence on the site. The windows are utilitarian, institutional, industrial, with frosted security glass containing wire that obscure a direct line of site into the structure. Within the pavilion is a single, dim light.

The pavilion sits immediately to the east of the entrance to the Meccanica development on the corner of First Avenue and Quebec Street in Vancouver, BC. The design borrows from the art-deco influenced electrical substations that are interwoven in Vancouver’s urban fabric. The piece looks as if it has been a long-term tenant of the site, as if it belongs to the area and is a relic of an earlier age. The illusion of its permanence is ruptured by a number of elements that disturb a simple and seamless inclusion in the local vernacular. The pavilion’s design references utility and yet as a consequence of the breaking up of vertical relations within the piece it becomes obvious something else is going on. What possible use could be made of a structure that seems to have no level floor, let alone barely enough room to turn around in? Why would so much attention be paid to the design of such a small and inconsequential piece of infrastructure?

Substation Pavilion’s design hints at the networks of subterranean connections with the rest of the city and with the past of the site itself. The entire area of False Creek consisted of a marshy wetland prior to its infill. This program of ‘reclaiming’ the tidal areas of Vancouver allowed for the development of the rail yards and industrial infrastructure at the east end of False Creek. This established a horizontal approach to looking at and moving through the growing city, tied as it was to these rail lines. The vertical tendencies of this project aim to introduce the rupturing the quotidian relationship with the horizontal that dominates movement through the city.

The strata formed in the soil of the False Creek area carry the history of the settlement of the area. The networks of the rail yards spread the stories of the people passing through them, creating layers within the cultural memory of the city. Over the years this cultural detritus molds and rots just as the soil and the structures of the area do. Together they form a humus that contains the mold that supports life in the city, spreading underneath every structure we build and every story we tell. This is a fertile substrate, not one given to decay and destruction. It supports connections and unexpected developments, much as the rhizomorphic systems of a large fungus will remain hidden, spreading underground and only exhibiting its presence once a year with its short-lived mushroom heads. It is a constantly shifting and ever-present narrative running just below the surface of the city.

Cedric Bomford

October, 2014